“Innocent sleep. Sleep that soothes away all our worries. Sleep that puts each day to rest. Sleep that relieves the weary laborer and heals hurt minds. Sleep, the main course in life's feast, and the most nourishing.”

William Shakespeare, Macbeth

Sleep in Extreme Environments: Part One.

(Adobe.)

Background & Significance

An Extreme Environment is a habitat characterized by harsh environmental conditions, beyond the optimal range for the proliferation, development, and survivability of humans. It is a term that is often misconstrued due to a stigmatized perception. In 2022, an extreme environment is not only synonymous with planet earth’s most-extreme physical environments; the new world around us is in fact a modern-era extreme environment due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, conflict, displacement, domestic and intimate partner violence, etc. With this perspective, the significance of this research can essentially be applied across a vast spectrum of extreme or ICE (Isolated, Confined, and Extreme) environments. For this paper, I will focus on how mental and physical health is affected in extreme environments.

The study of extreme environments is an exploration of the limits of life that exist both on our home planet and amongst the stars above. One must keep in mind that there is a stark difference between living in extreme environments versus tolerating an extreme environment; though, both situations can help us understand how extreme environments affect life. The adaptations that allow organisms to live or survive extreme environments are in fact a valuable target of study because they allow us to have a better understanding of life's basic processes and how life responds to environmental challenges (Boyd et al., 2016).

The takeaway helps us to “learn vital lessons on how to grow food, process waste, habitat restoration, and perform other important tasks to support our ability to survive and thrive in extreme environments” (Boyd et al., 2016). In 2022, we as humans are in a race to become a multi-planetary species. With this in mind, the study of extreme environments is more relevant than ever. As interplanetary exploration missions continue, we are learning that we can train on planet earth’s diverse environments in order to survive on other worlds such as Mars, and other exoplanets that we are continuously discovering.

(Frontiers | Living at the Extremes: Extremophiles and the Limits of Life in a Planetary Context, n.d.)

Types and Examples of Extreme Environments

Acidic: natural environments below pH 5 whether persistently, with regular frequency, or for protracted periods of time (Types of Extreme Environments, n.d.).

Extreme Cold: environments that are periodically or consistently below 5°C either persistently, with regular frequency, or for protracted periods of time (Types of Extreme Environments, n.d.).

Extreme Heat: environments that are periodically or constantly in excess of 40°C either persistently, with regular frequency, or for protracted periods of time (Types of Extreme Environments, n.d.).

Hypersaline: (high salt) environments with salt concentrations greater than that of seawater, that is, >3.5% (Types of Extreme Environments, n.d.).

Under Pressure: environments under extreme hydrostatic pressure —i.e. aquatic environments deeper than 2000 meters and enclosed habitats under pressure (Types of Extreme Environments, n.d.).

Radiation: environments that are exposed to abnormally high radiation or radiation outside the normal range of light (Types of Extreme Environments, n.d.).

Without Water: environments without free water whether persistently, with regular frequency, or for protracted periods of time (Types of Extreme Environments, n.d.).

Without O2: environments without free oxygen - whether persistently, with regular frequency, or for protracted periods of time (Types of Extreme Environments, n.d.).

Humans Altered: heavy metals, organic compounds; anthropogenically impacted environments (Types of Extreme Environments, n.d.).

Astrobiology: addresses life beyond the known biosphere—inclusive of life on other heavenly

bodies, in space, etc. Includes terraforming (Types of Extreme Environments, n.d.).

Examples of Extreme Environments

Submarines and Underwater Habitats.

Space Analog Simulations, and Actual Spaceflight.

Desert, Tropical, and Ocean (world’s largest desert).

Military Combat and Front-Line and High-Conflict Zones.

Modern-era Pandemic (isolation and lock-down) and Post-Pandemic Society.

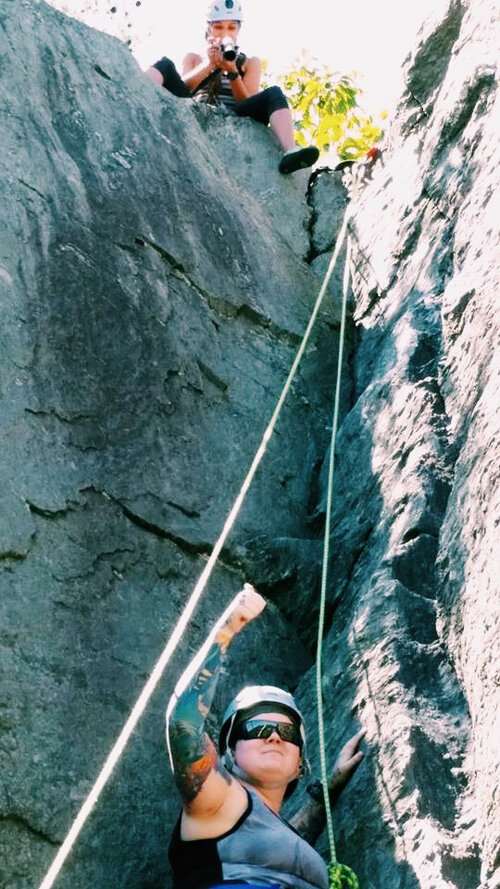

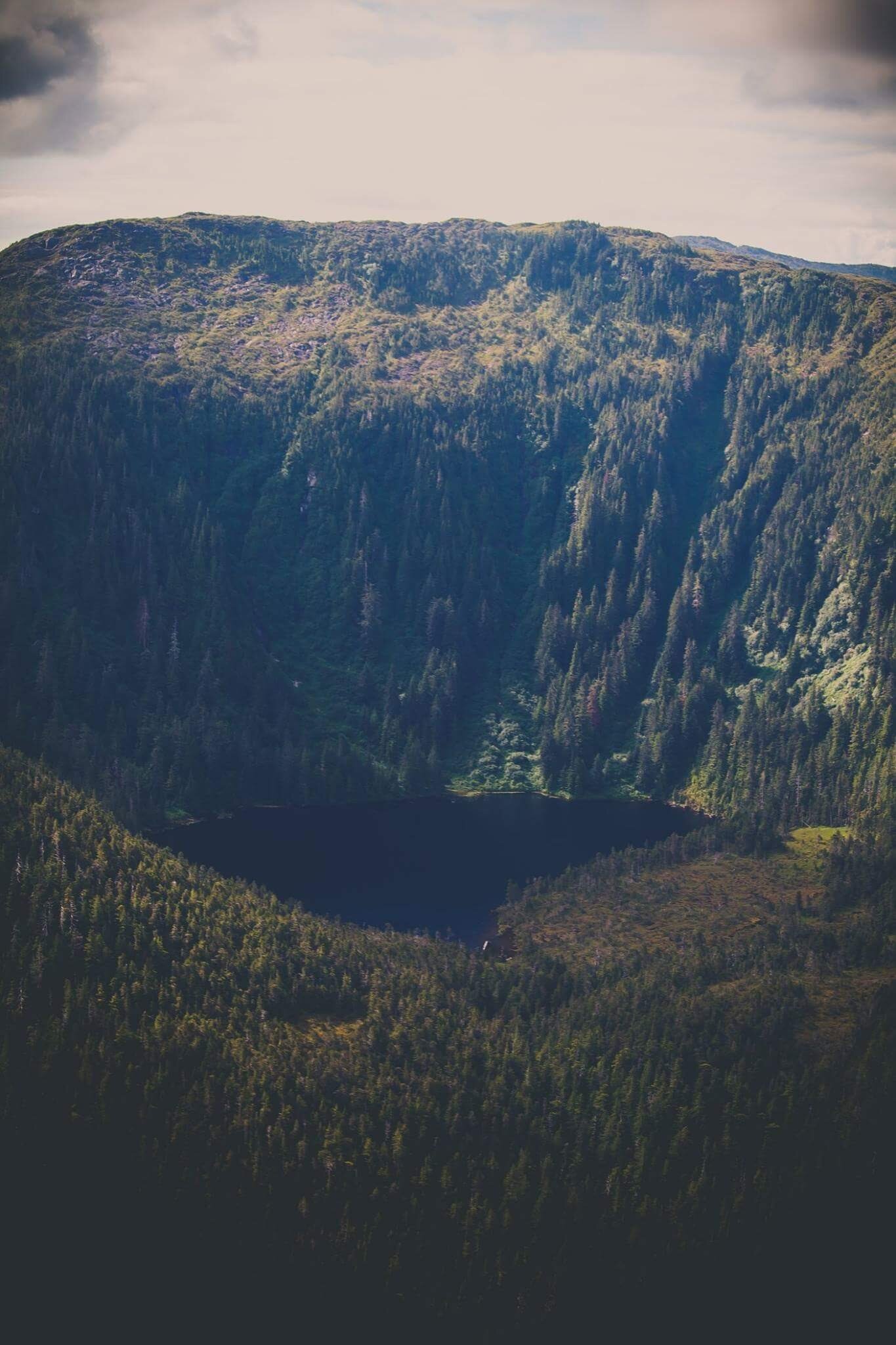

High-Altitude (Mountaineer and Stratospheric Flight).

Altered Light and Dark Cycles.

High Radiation and Microgravity.

Isolation, Social Isolation, and Confinement.

Caves and Karst.

High-Pressure and Hypobaric Chambers.

Interplanetary Travel.

Air Pollution and Wildfires.

Long-Duration Expeditions.

Extreme Shift-Work (light and dark cycle dysregulation).

Long-Duration Polar Expeditions and Polar Habitats.

(Wylde, n.d.)

Physiological and Psychological Effects of Extreme Environments

Various adaptive biological processes can take place to cope with the specific stressors of extreme terrestrial environments like cold, heat, hypoxia (high-altitude) and ICE (Isolated, Confined, and Extreme). Examples of the physiological effects that humans face in an extreme environment are:

- Stationary (stagnant) exhibits baseline level personality dysregulation.

- Circadian rhythm desynchronization.

- Sleep disturbances.

- Changes in peripheral circulation; hypothermia; and frostbite.

- Hypoxia and altitude-induced cardiopulmonary symptoms.

- Headaches.

- Deficiency of carbon dioxide in the blood.

- Hyperventilation

- Suppression of immune system

- Disruption of thyroid function.

- Light and dark-cycle disturbances.

- Absence of viral and bacterial agents.

- Increase in hormonal dysregulation.

- Increase in cortisol.

- Sleep deprivation.

- Vestibular and sensorimotor alterations.

- Expeditionary (deployments and combat) which induces high dopamine.

Changes in the physical environment have been shown to produce changes in the psychosocial issues confronting crews operating in extreme settings. This has the potential to produce symptoms of depression, insomnia, irritability or anger, anxiety and tension-anxiety, confusion, fatigue, and decrements in cognitive performance. Additionally, sleep impairment and sleep deprivation that contribute to psychopathology are known to be major causes of the breakdown of personal, and interpersonal conflict, tension, and group/team cohesion.

Disruptions in sleep are known to produce brain fog and brain inflammation which also induce psychopathology. These symptoms run the risk of producing cognitive, and behavioral conditions; and psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, depression, adjustment disorder, and acute psychosis all of which are responsible for impaired thought-process and performance errors.

“Individual issues include changes in emotions and cognitive performance; seasonal syndromes linked to changes in the physical environment; and positive effects of adapting to ICE environments. Interpersonal issues include processes of crew cohesion, tension, and conflict; interpersonal relations and social support; the impact of group diversity and leadership styles on small group dynamics; and crew-mission control interactions. Organizational issues include the influence of organizational culture and mission duration on individual and group performance, crew autonomy, and managerial requirements for long duration missions” (Palinkas & Suedfeld, 2021).

Furthermore, some extreme environments can produce seasonal variations in mood and somatic complaints, mostly due to lack of natural sunlight, extreme weather, and free access to move about in the environment. An example of this would be space and high-pressure environments that would force humans to remain within their habitat for long periods of time.

Winter-Over Syndrome is a cluster of symptoms of sleep disturbance, impaired cognition, negative affect, and interpersonal tension and conflict (Palinkas & Suedfeld, 2021).

Polar T3 Syndrome is an alteration of mood and cognition related to thyroid function (Palinkas & Suedfeld, 2021).

Subsyndromal Seasonal Affective Disorder occurs when extreme variations in the patterns of daylight and darkness in high latitude induce behavioral symptoms which disrupt circulating melatonin concentrations, a major transducer of photoperiod information for the timing of multiple circadian and circannual physiologic rhythms (including rhythms of energetic arousal, mood, and cognitive performance) (Palinkas & Suedfeld, 2021).

(NASA.)

Stress in Extreme Environments

“The Right Stuff” was a term coined based upon the characteristics of the mission which could define who will be successful (adaptation) and who is prone to (possible) failure (maladaptation). “These factors could impair mood or cognition: prolong depression, induce episodes of anxiety, social withdrawal, interpersonal tension and hostility, poor leadership, miscommunication and human error” (Palinkas & Suedfeld, 2021). Both survival and performance require coping with environmental stressors by adaptive biological processes of various kinds, which are adaptation, acclimatization, acclimation, and habituation (Burtscher et al., 2018).

Acclimatization is initiated by exposure to extreme natural environments of previously not-exposed individuals and occurs gradually within days to weeks, sometimes even months, enabling maintenance of performance. “Acclimation involves adaptive processes induced by exposures to habitats, where specific types of extreme conditions are simulated in order to achieve acclimatization for later exposure to naturally occurring extreme habitats” (Burtscher et al., 2018). “Habituation defines the process of reducing physiological and psychological stress responses upon repeated stimuli, (e.g. improved tolerance)” (Burtscher et al., 2018). Repeated and/or prolonged exposure to stressors in extreme environments can fuel psychological and physiological dysregulation, as well as accelerate degenerative conditions (e.g. cancer, Alzheimer's, and immunodeficiencies).

Taking an aggressive whole-body approach will support an individual's own return back to baseline homeostasis and allow them to survive or thrive in extreme environments.

“The DMZ or Demilitarized Zone, the border between North and South Korea is one of the most heavily guarded stretches of land in the world — a band 2½ miles wide and 150 miles long dividing the peninsula since the Korean War ended in 1953. The DMZ, littered with scores mines and barbed-wire fences, is nightmarishly difficult to cross, except here in the Joint Security Area, a special buffer zone about 35 miles north of Seoul”. (Boling, Imagery Beyond Borders, 2009).

“Military-relevant stressors and the gut microbiota. Military personnel can be exposed to extremes and combinations of psychological, environmental (e.g., altitude, heat, cold, and noise) and physical (e.g., physical activity, sleep deprivation, and circadian disruption) stressors. These stressors induce central stress responses that ultimately alter gastrointestinal and immune function which may lead to changes in gut microbiota composition, function and metabolic activity. Other stressors such as diet, enteric pathogens, environmental toxicants and pollutants, and antibiotics can alter gut microbiota composition and activity through direct effects on the gut microbiota, and indirectly through effects on gastrointestinal and immune function. Stress-induced changes in the gastrointestinal environment may elicit unfavorable changes in gut microbiota composition, function and metabolic activity resulting in a dysbiosis that further compromises gastrointestinal function, and facilitates translocation of gut microbes and their metabolites into circulation. Alternately, evidence suggests that some stressors (e.g., healthy diet, cold, and physical activity) may favorably modulate the gut microbiota. To what extent these changes impact the health, and physical and cognitive performance of military personnel is currently unknown” (Karl et al., 2018).

References

Boling, Melanie. (2022). Melanie Noelani Boling. Imagery Beyond Borders. https://imagerybeyondborders.org

Boling, Melanie (2021). Reported results of Amazonian Entheogens for treatment of Complex-Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD); Military Sexual Trauma (MST); and Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) among U.S. Military Veterans and the benefits of application through small group indigenous shamanic ceremonies. The Amazon Rainforest: From Conservation to Climate Change-research. Harvard Summer School, August 9, 2021

Buguet, A. (2007). Sleep under extreme environments: Effects of heat and cold exposure, altitude, hyperbaric pressure, and microgravity in space. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 262(1–2), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2007.06.040

Concordia crew 2014-2015. (n.d.). Retrieved August 3, 2022, from https://www.esa.int/ESA_Multimedia/Images/2016/07/Concordia_crew_2014-2015

Frontiers | Living at the Extremes: Extremophiles and the Limits of Life in a Planetary Context. (n.d.). Retrieved August 1, 2022, from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00780/full

Introduction to Psychology in Extreme Environments. (n.d.). Retrieved August 5, 2022, from https://inextremis.teachable.com/p/introduction-to-psychology-in-extreme-environments

Karl, J. P., Hatch, A. M., Arcidiacono, S. M., Pearce, S. C., Pantoja-Feliciano, I. G., Doherty, L. A., & Soares, J. W. (2018). Effects of Psychological, Environmental and Physical Stressors on the Gut Microbiota. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02013

Loff, S. (2016, July 22). Aquanauts Splash Down, Beginning NEEMO 21 Research Mission [Text]. NASA.

Palinkas, L. A., & Suedfeld, P. (2021). Psychosocial issues in isolated and confined extreme environments. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 126, 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.03.032

Perez, J. (2020, June 11). What Can We Learn About Isolation From NASA Astronauts? [Text]. NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/feature/isolation-what-can-we-learn-from-the-experiences-of-nasa-astronauts

Wylde, E. (n.d.). Extreme Environmental Physiology: Life at the Limits. The Physiological Society. Retrieved August 5, 2022, from https://www.physoc.org/events/extreme-environmental-physiology/

About the author:

Melanie began attending Harvard in 2020 to complete a Graduate Certificate in Human Behavior with a specialization in Neuropsychology. Boling’s research has examined extreme environments and how they can have a potential negative impact on humans operating in the extreme environment. During her time at Harvard, she has built a mental wellness tool called a psychological field kit. Implementing these tools will allow an individual to thrive in an extreme environment while mitigating negative variables such as abnormal human behavior which can play a role in team degradation.

Melanie Boling, Extreme Environments Neuroscientist and Photojournalist, Boling Expeditionary Research.

Melanie Boling is also a Graduate Student of Neuropsychology and Journalism at Harvard University. She is a Founder and CEO to International NGOs Imagery Beyond Borders and Peer Wild. Boling recently opened her Behavioral Neuroscience Field Research and Consulting Business, Boling Expeditionary Research.